In August 1835, a New York newspaper called The Sun published a story so strange, so exciting, that it captured the imagination of readers all over the country. It wasn’t about politics or crime—it was about the Moon. According to the article, a famous British astronomer named Sir John Herschel had discovered life on the Moon using a massive telescope in South Africa. The newspaper said it got this incredible story from the Edinburgh Journal of Science, a respected science magazine. But the journal didn’t even exist anymore.

Still, readers believed it. The tale became one of the biggest hoaxes in newspaper history, known today as The Great Moon Hoax.

Creatures of the Moon

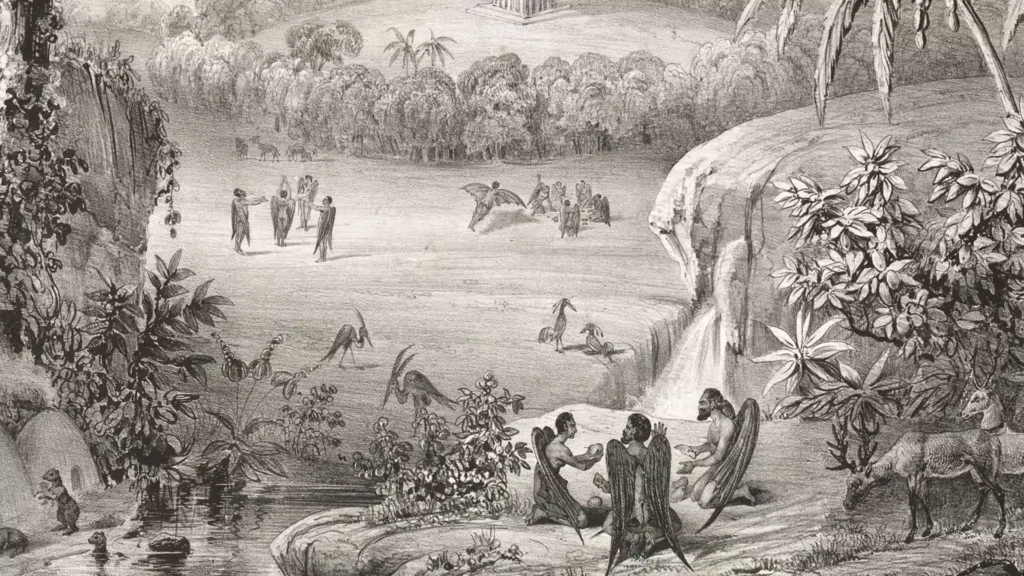

The story wasn’t just about craters or rocks. The articles described an entire world full of life. According to Wikipedia, the Moon was home to animals like bison, mini zebras, single-horned goats, and even unicorns. But the most unbelievable part? There were “Vespertilio-homo”—humanoid, bat-like creatures that walked on two legs, built temples, and behaved in a “dignified” manner.

One article painted a vivid image:

“Certainly they were like human beings, for their wings had now disappeared, and their attitude in walking was both erect and dignified … they averaged four feet in height, were covered, except on the face, with short and flossy copper-colored hair, and had wings composed of a thin membrane, without hair, lying snugly upon their backs…”

These beings lived in a magical-sounding landscape filled with purple crystals, wide rivers, and forests, all seen through a powerful telescope said to be 24 feet wide and weighing seven tons. But no telescope like that existed in the 1830s. Not even close.

A Fake Scientist and a Real Trick

The articles were credited to someone called Dr. Andrew Grant, who was described as Herschel’s assistant. But this person didn’t exist. The real writer was most likely Richard Adams Locke, a reporter for The Sun who had studied at Cambridge University. He later admitted that he wrote the story, possibly as a joke or as a way to mock earlier writers who claimed there were people on other planets.

One of those writers was Reverend Thomas Dick, who believed billions of people lived on the Moon. Locke may have thought his version was clearly too wild to be taken seriously. But he was wrong.

A Nation Believes

When the first article appeared on August 25, 1835, the public went wild with excitement. People crowded newsstands to get the latest installment. Even some educated readers thought the story might be true. According to reports, scientists from Yale University went to New York City to find the original articles from the Edinburgh Journal. Instead of answers, they were sent on a wild chase by The Sun’s staff.

Famous people reacted, too. P.T. Barnum, the showman known for his own stunts, called it

“the most stupendous scientific imposition upon the public that the generation with which we are numbered has known.”

Even Edgar Allan Poe, the writer of mystery and horror stories, suspected it was fake. According to NBC New York, Sir John Herschel himself was first amused by the story, but later grew tired of being asked about the bat-people. He eventually called the hoax “incoherent ravings.”

Why the Hoax Worked

At the time, newspapers were changing. The Sun was one of the first “penny papers,” selling for just one cent and aimed at working-class people. Its stories were meant to entertain as much as inform. During this period, New York City was full of arguments over slavery, politics, and poverty. This Moon story gave people something totally different—something fun to believe in.

Benjamin Day, The Sun’s publisher, later admitted that the hoax helped “divert the public mind” from more serious problems.

Although John Herschel really did go to South Africa in 1834 to build a telescope and study the stars, nothing he did even came close to what The Sun claimed. The telescope in the hoax was pure fiction. There was no 24-foot lens or Moon creatures being seen through it.

Still, the articles described every made-up detail with care. History.com says the reports even mentioned amethyst crystal formations, waterfalls, and forests—none of which exist on the Moon. But because it all sounded so detailed and scientific, people accepted it.

The Truth Comes Out

The final article in the series ran on September 16, 1835, and by then, The Sun finally admitted the story was fake. Surprisingly, people weren’t very angry. Most had enjoyed the ride. Some might have even felt a little foolish, but they still appreciated the entertainment.

The Great Moon Hoax became a landmark moment in journalism. It showed how easy it was to mix fact and fiction—and how eager people were to believe stories that amazed them. It also helped push newspapers to think more seriously about checking facts and being honest with readers.